- Home

- Keri Arthur

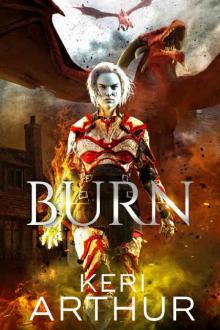

Burn Page 2

Burn Read online

Page 2

“Is that where you plan to escape?”

He raised an eyebrow and didn’t reply. Which was frustrating but understandable, given his distrust. Truth be told, had our positions been reversed, I wouldn’t even have said as much as he had.

Silence fell, and time ticked by very slowly. The air in the pod grew colder, suggesting night was drawing in. Eventually, from beyond the metal confines of our prison, came the rise and fall of conversation, though what they were saying was muted and garbled. But the accent came through loud and clear, and it held none of the more rhythmic lilt of the Arleeon. It was instead filled with the guttural sharpness of the Mareritt.

Tension wound through me. I had to be mishearing. The ice scum couldn’t have succeeded in their quest to claim any part of Arleeon. Zephrine might have fallen, but why would Esan have also capitulated? The might of the drakkon had held the Mareritt at bay for as long as drakkons and their riders had existed—why would their strength have failed now? What had happened? What couldn’t I remember?

Our transport came to a halt. Metal rattled as the other captives moved restlessly, their gazes darting to the sharper end of the pod. The guttural tones grew louder, closer. I clenched my fists against the growing tension, but fire burned deep within and it was begging for release—and that was impractical in this crowded prison pod. I breathed deep in an effort to relax. It didn’t help.

A crack of light appeared at the base of the pod’s nose and spread in a sweeping arc—it was a door, one that slowly moved forward and then up.

The other men and women in the pod stilled, but the rush of their fear and uncertainty swamped me. The latter emotion was one I shared. It very much felt like I was teetering on the edge of a precipice, about to fall into a darkness that was deep and unending.

A figure stepped into the doorway. With the bright hues of a golden sunset behind him, he was little more than a silhouette—one with shoulders almost too wide for the door and a build so chunky he could have been a deep-earth miner. But there were six fingers on his hands rather than five, and the tips of his short, spiky hair gleamed like blue ice against the warmer colors of the sunset.

Mareritt.

Anger and hatred hit so hard that, for an instant, I could barely breathe. Heat burned through me, around me, and all I saw was red. Instinct had me rising, but a hand came down on my leg, pressing me back. Holding me still.

“Don’t,” the warrior hissed. “Keep your eyes down, and don’t react to anything if you want to live.”

I could feel his gaze on me.

Knew the Mareritt was also watching.

I swallowed my anger and fought for control. Reacting on instinct and emotion might have gotten me out of trouble in the past, but in this case, it would only get me into it. Aside from the fact that I was chained hand and foot to the warrior, I had no idea where I was. Both common sense and training suggested I bide my time and get the lay of the land before I did anything.

But common sense was hard to grip when I remembered all those who’d been tortured and killed at the hands of the frost scum.

And if I could remember that, why in the wind’s name couldn’t I remember how I’d gotten here or who I was?

I dropped my head and took another deep breath. Tried to ignore the thick scent of musk that was the Mareritt. Tried to act as broken as everyone else in this pod when all I wanted to do was flame and cinder.

“Up,” the Mareritt growled. “Fall into two-by-two formation.”

Chains rattled as everyone obeyed. I pushed to my feet, felt the cuff around my ankle bite into my skin as the warrior did the same. The Mareritt pressed a panel to the left of the door, and the shackles around our ankles unclasped, rattling loudly as they hit the floor.

“Follow the yellow line,” he continued. “Eyes down. No talking. No straying.”

The farmers and the women began shuffling out of the pod. I kept my eyes down as ordered but was very aware of both the frost scum and the growing tension in the man walking by my side. The closer I drew to the Mareritt, the stronger his stink became. My heart was beating so fiercely, so loudly, it sounded like a battle drum. I wanted to reach out, to grasp his thick neck and squeeze it until his dark eyes popped from his head. But that was the fire within my soul speaking, not the human who knew better.

Closer still... Heat surged, a force so fierce the air briefly shimmered. I held on tight to the power burning through my veins. Now was not the time to release—and not just because there would be more than one Mareritt soldier in this place. I was chained to the warrior and walked too close to the farmers and the women. Any action on my part would rebound back to them. My internal fires might not affect me, but these people had been abused enough; I dared not add to their suffering.

I clenched my hands and kept my eyes down. The Mareritt’s stink clogged every breath and made the fire in my blood burn brighter. I wanted to strike; wanted to cinder his ass and leave nothing behind but the smoking remnants of his thick leather boots. Somehow, I forced one foot after the other, moving past him and onto the metal ramp that linked the pod to the ground.

The need to flame didn’t ease. There were too many other Mareritt in this place. I could feel them—smell them.

I continued forcing one foot in front of the other. The metal ramp gave way to shiny blue-black stone; it was a substance found in the Blue Steel Mountains, the “spine” portion of the vast range that ran from Zephrine to Esan, separating Arleeon from Mareritten. The stone was prized for its strength and its imperviousness to weather, but it was so difficult to mine that few in Arleeon used it. Obviously, the Mareritt had succeeded where we’d failed—and were now using Arleeon prisoners as their workforce, if the previous comments by the man walking next to me were anything to go by.

The yellow line appeared. The other prisoners dutifully followed it but were nevertheless watched by quite a number of Mareritt if the boots I was seeing were anything to go by. I wished I dared look up; I desperately wanted to see Break Point Pass. Was it Esan, renamed? And yet how was that even remotely possible? I couldn’t believe both fortresses had fallen—and even if they had, why would they rename it and not Zephrine? And why would an Arleeon warrior use the term?

The wind drifted past my nostrils, carrying distant scents to me. It spoke of a large settlement, one that was used by both Arleeon and the frost scum, and the confusion within me grew. Why would anyone willingly live side by side with the Mareritt? It made no sense given what I knew about either race and only made the disconnect between my admittedly fragmented memories and what I was sensing and seeing stronger.

The yellow line curved to the left. I raised my gaze a little; the buildings around me were as squat as the men who’d no doubt built them and clung in layers to the smooth sides of a mountain that rose almost vertically from the ground. None of the buildings were very deep—perhaps they were the preface of a larger settlement lying within the heart of the mountain. It wasn’t Esan, but that realization didn’t ease my fear. Quite the opposite, in fact.

To my right lay a vast wall and gates made of a metal that gleamed like rusted blood in the fading light of the evening. Those gates were open; the road beyond led the eye to a land that was broken but green and then arrowed on toward snow-capped mountains.

I knew that landscape, even if the city around me was unfamiliar. It was Mareritten, the home of the frost scum—a land that was a vast subarctic wilderness, and one in which the conditions were so harsh that for nine months of the year its people sought shelter in underground cities and drew on the heat of distant volcanoes to survive. And yet how was that possible if we were still in Arleeon? Had the warrior misled me? Had we been in Mareritten all the time, and Break Point Pass was merely an overnight stop on the way to Frio, the Mareritten capital?

No, some inner instinct whispered.

The yellow line now ran in the same direction of the blood-colored metal wall. Despite the number of Mareritt watching us, there were no guards on that wal

l, which was odd—why build it at all if you weren’t going to keep watch? Mareritten might be a harsh and inhospitable land for a good part of the year, but that had never stopped those from beyond our continent seeking to control its mineral wealth.

Up ahead, a vast metal door began to open, revealing a space that was as black as the sheer sides of the mountain that now reared above us. Our prison, it seemed, was a deep cavern rather than any kind of regular cell.

Old fears stirred at the thought of being locked in underground darkness. I took another of those deep breaths that did little to help and raised my gaze to the fading but still glorious sunset. As I did, a bugle echoed. It was a deep and haunting sound, one that came not from any man-made instrument but rather a creature who’d ruled the skies since time immemorial.

My heart leapt and joy swept through me.

High above us, perched on an outcrop of rock that jutted out from the otherwise sheer sides of the mountain, was a drakkon. Her leathery wings were outstretched, dwarfing her body, the membrane between the four main phalanges glowing gold. Her long tail draped down the rock face like liquid fire, and her broad head was raised as she called in the arrival of night.

But as her haunting cry echoed around us once more, I noticed the figure standing beside her.

Shock coursed through me, and I stopped abruptly.

No, I thought. No.

I could perhaps accept Zephrine’s destruction. I could even contemplate the possibility that the Mareritt now controlled vast sections of Arleeon.

But never, ever could I accept what I was now seeing.

A drakkon in the hands of a Mareritt.

Two

This had to be a nightmare. Had to be.

If ever there was a universally accepted fact, it was that the Mareritt could not withstand the melding of minds required to become drakkon riders.

They’d certainly tried—Zephrine’s libraries were littered with reports of their raids on the aeries, some of which had been successful, many not. If the stolen eggs had remained viable in Mareritten’s subarctic clime, then those drakkons existed in a place far beyond the watchful eye of Arleeon’s many graces—the collective name for groups of drakkons. It was certainly possible, given the Mareritt lived underground for a good part of the year. Maybe they’d taken the time to build a viable fighting force before they’d unleashed them against Arleeon’s own drakkons.

But if that was what had happened, where were Arleeon’s riders? Why would they allow the frost scum to gain any sort of toehold within our lands?

None of this made sense. Absolutely none of it.

The farmer behind me thrust a hand into the middle of my back and sent me stumbling. I would have fallen had not the warrior yanked back on the chain that still bound us, holding me upright, steadying me.

“Thanks,” I muttered.

He didn’t respond. A wise move, given the nearest Mareritt had raised his weapon in warning and was now watching us both a little too closely.

But I didn’t lower my gaze. I couldn’t. It was almost as if, by continuing to stare, what I was actually seeing would somehow dissolve into what I was supposed to be seeing—a Zephrine warrior on the back of her drakkon, heralding the attack of a full grace.

Unfortunately, that didn’t happen. But as the drakkon bugled a third time, I noticed something else—her size. Full-grown drakkons were massive beasts—just over twelve feet tall and sixty feet long, with a wingspan close to one hundred and fifty feet. This drakkon was half that size—in fact, she was little bigger than the long-horned bovine that roamed across major parts of both the Baknurn and Garmain territories. There was no way known that Mareritt could ride her—she was simply too small to carry someone of his density. Hell, she might even struggle to lift me from the ground, and I’d been born to ride drakkons.

What in the wind’s name was going on?

It was tempting, so very tempting, to reach out to the drakkon and seek answers to the questions pounding through my soul. But I didn’t dare—if the Mareritt had somehow figured out a means of telepathically communicating with the drakkons, I’d basically be announcing my presence not only to her but also her handler.

I lowered my gaze and walked on into the cellblock. It had been carved out of the mountain’s blue-black stone and was oblong in shape. The fading light behind us lifted the shadows enough to reveal tiered benches of stone lining the wall to the right; to the left, halfway down the room, were a couple of privies. These were partially shielded by a single straight wall that was barely three feet tall; it wouldn’t have offered much in the way of privacy, especially if you were tall. Which I was—a long and lanky build was something of a necessity for drakkon riders.

Or it had been, until the Mareritt had somehow gained control of the drakkons.

I pushed back the confusion and the questions that rose with the thought and continued studying our prison. A small fountain to the left of the privy area provided some water, but there was little else. There were no blankets, pillows, or anything else that could have eased the discomfort of this place. And while that was no surprise given it was a prison cell, even the most rudimentary cell in Zephrine offered blankets and a basic mattress. Or they had, before the world turned upside down.

The warrior tugged on the chain to capture my attention and then motioned toward a low bench closest to the door. I followed him across and sat next to him, my back against the wall and my knees drawn up close to my chest. I wasn’t cold—the fire in my veins was more than enough to chase away the chill of this place—but the guard at the door continued to watch me. Giving the appearance of defeat rather than defiance was the wiser option right now.

Once the last of the farmers had filed into the cavern, several small tubs were carried into the room and placed in the middle of the floor. The delicious aroma of bread and cheese permeated the room, and my stomach rumbled noisily. No one moved toward the food, however—not even when the Mareritt motioned to the tubs with his gun. He snorted, the sound one of contempt, and backed out. The door immediately slammed shut. Two spots of pale light began to glow, one above the door and one down the far end of the room. They didn’t turn night into day, but they did at least provide enough light for people to move around without fear of running into someone or something.

But for several more minutes, everyone remained where they were. Then, one after the other, the farmers shuffled toward the food. My stomach continued rumbling, but I did my best to ignore it. I might be hungry, but there was no way known I’d eat anything provided by the Mareritt.

I looked away from them and spotted a lone monitor on the wall above the privy area. It was doing slow sweeps of the entire cavern, from the door to the deepest point of the oblong.

“We’re being watched,” I murmured.

“Yes. The Mareritt have little trust for anyone but their own.”

“Why, when they very much appear to have the upper hand?”

He shrugged. “Because resistance still exists, for all their efforts to extinguish it.”

“You have no idea how happy I am to hear that.” I pulled my gaze from the camera and watched a couple of the older men take control of the tubs and start divvying out the food. It was all done in utter silence, with motions to convey directions rather than words. “I take it these men and women are not part of that resistance?”

“No. The Tarlien capital lies well within the occupied territories, and that gives us only two choices—either accept Mareritt rule, or die. There is no in-between.”

“There obviously is, if you’re a part of the resistance.”

He glanced at me, a warning in his bright eyes. Of what, I wasn’t entirely sure. “None of us are part of the resistance—we’re farmers. Nothing more, nothing less. You place words into my mouth, ice maiden.”

“Why do you insist on calling me that?” The annoyance in my voice was real enough. “I’m no Mareritt—and the fact that I’m here, chained to you, should be evidence enough of that.

”

He raised a dark eyebrow, disbelief evident. “As I’ve said previously, the Mareritt work in mysterious ways. But if you make enough denials, I might be tempted to not only believe you but trust you.”

He might not believe my denials, but, rather weirdly, I had an odd sense that he did now trust me. Up to a point, anyway. I had no idea why, but I wasn’t about to question the change. If I was to have any chance of escaping the Mareritt and uncovering the truth of what was going on, then I needed an ally—someone who at least understood the world I seemed to have fallen into.

“If none here are part of the resistance, why are they prisoners? It makes no sense given how vital the farmlands—and experienced workers—are.”

“There was an attack on a supply train. The raiders escaped, but we now pay the price for being in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Which was a variation of what he’d already said in the prison pod, only this time with him being placed in the role of a farmer rather than aggressor. I opened my mouth to ask why, then closed it again as the warning in his eyes got stronger.

We’re being listened to, that look seemed to say. Change the subject.

Which was a rather odd perception on my part. That sort of unspoken understanding generally only existed between kin and their drakkons, and he couldn’t be kin simply because he was male. The ability to bond with drakkons had only been ceded to the females of the first ancestor’s line.

I frowned and glanced back at the camera. After a second, I saw the bulbous lump underneath it. A sound receiver, though one far sleeker than anything I’d ever seen.

One of the farmers cleared his throat, then, when we glanced across, tossed a small loaf of bread and a bit of cheese our way.

“Hungry?” the warrior asked as he caught the two items.

“No.”

“Neither am I.” His gaze flicked from mine to the monitor and then back. “But given we have no idea when we’ll get the next meal, I suggest we at least try to eat.”

Kissing Sin

Kissing Sin Darkness Falls

Darkness Falls Hell's Bell

Hell's Bell Moon Sworn

Moon Sworn Beneath a Rising Moon

Beneath a Rising Moon The Darkest Kiss

The Darkest Kiss Dancing with the Devil

Dancing with the Devil Lifemate Connections: Eryn

Lifemate Connections: Eryn The Black Tide

The Black Tide Embraced By Darkness

Embraced By Darkness Deadly Desire

Deadly Desire Tempting Evil

Tempting Evil Kiss The Night Goodbye

Kiss The Night Goodbye Bound to Shadows

Bound to Shadows Circle of Desire

Circle of Desire Dangerous Games

Dangerous Games Full Moon Rising

Full Moon Rising Circle of Fire

Circle of Fire Darkness Rising

Darkness Rising Deadly Vows

Deadly Vows Darkness Devours

Darkness Devours Penumbra

Penumbra Who Needs Enemies

Who Needs Enemies Cursed (Kingdoms of Earth & Air Book 2)

Cursed (Kingdoms of Earth & Air Book 2) Hearts in Darkness

Hearts in Darkness Darkness Hunts

Darkness Hunts Wicked Wings (The Lizzie Grace Series Book 5)

Wicked Wings (The Lizzie Grace Series Book 5) Circle of Death

Circle of Death Chasing the Shadows

Chasing the Shadows Darkness Splintered

Darkness Splintered Ashes Reborn

Ashes Reborn Demon's Dance

Demon's Dance Blackbird Rising (The Witch King's Crown Book 1)

Blackbird Rising (The Witch King's Crown Book 1) Winter Halo

Winter Halo Wicked Wings

Wicked Wings Kiss the Night Good-bye

Kiss the Night Good-bye Destiny Kills

Destiny Kills Mercy Burns

Mercy Burns Beneath a Darkening Moon

Beneath a Darkening Moon Demon's Dance (The Lizzie Grace Series Book 4)

Demon's Dance (The Lizzie Grace Series Book 4) Burn

Burn Unlit_A Kingdoms of Earth & Air Novel

Unlit_A Kingdoms of Earth & Air Novel Blackbird Broken (The Witch King's Crown Book 2)

Blackbird Broken (The Witch King's Crown Book 2) Cursed

Cursed Unlit

Unlit